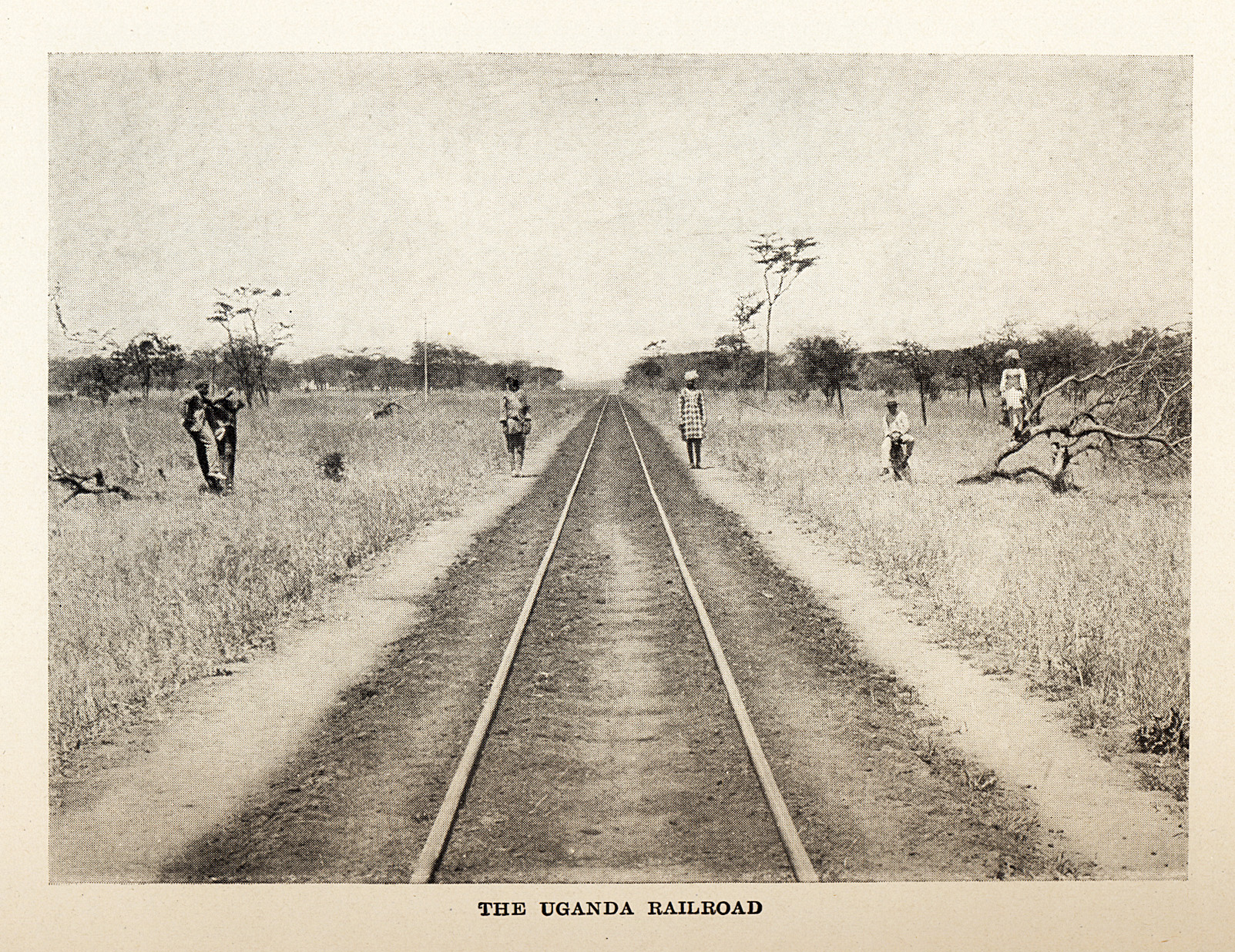

Uganda Railway

From Percy C. Madeira, Hunting in British East Africa (J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and London, 1909).

Photo: Newland, Tarlton & Co.

From Percy C. Madeira, Hunting in British East Africa (J. B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia and London, 1909).

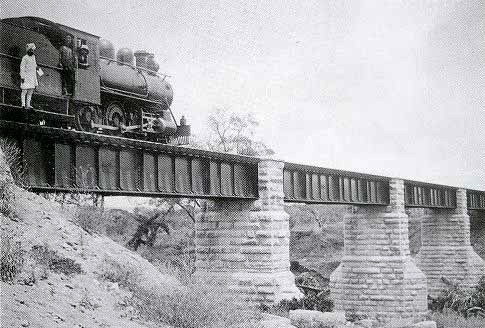

Courtesy of transpress New Zealand (www.transpressnz.com)

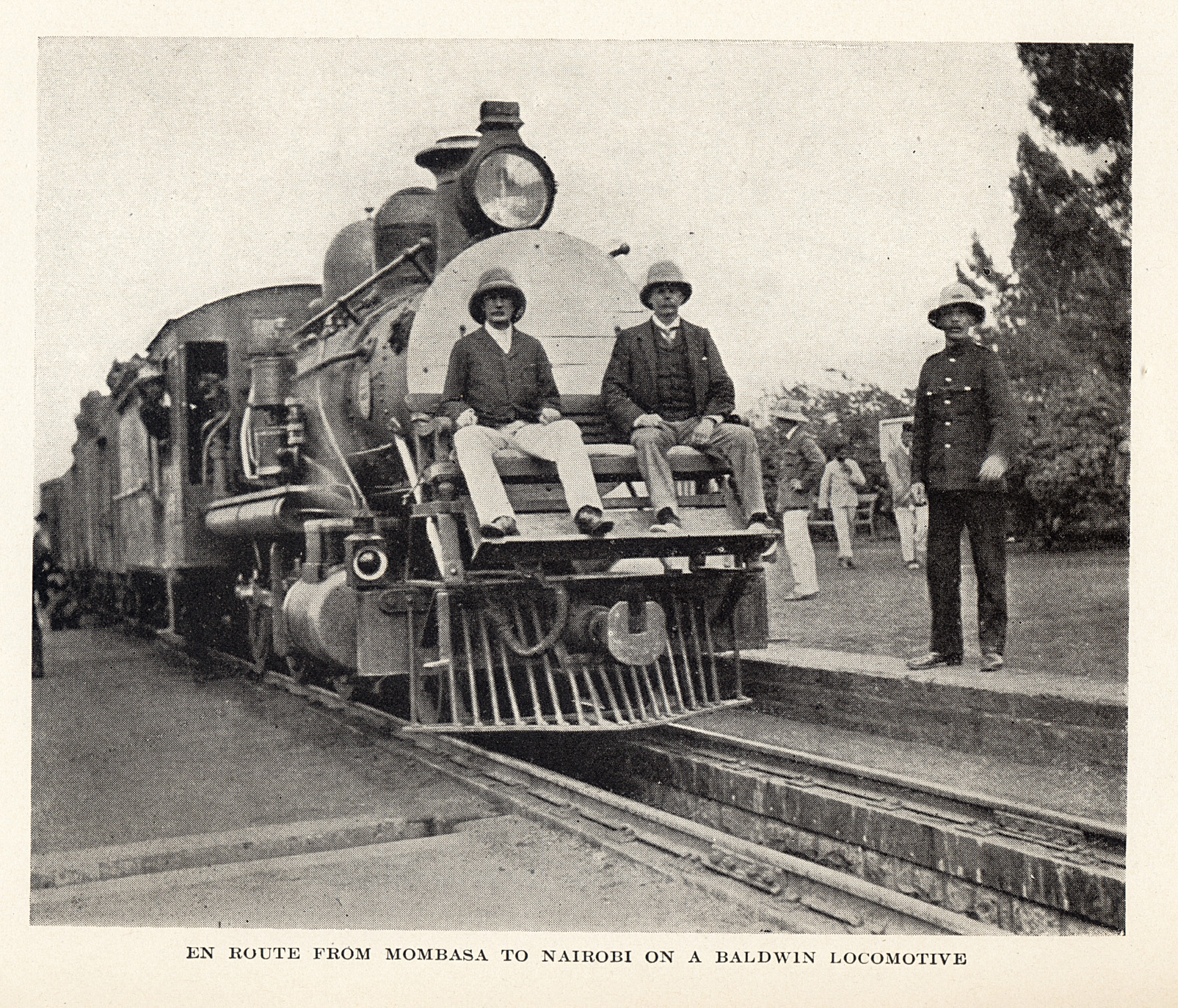

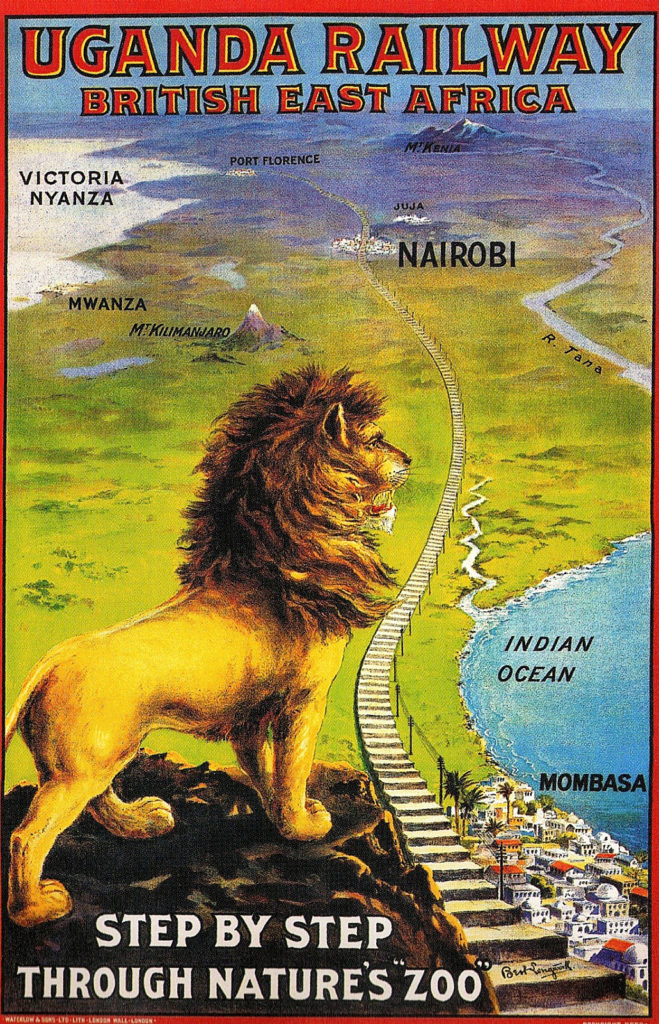

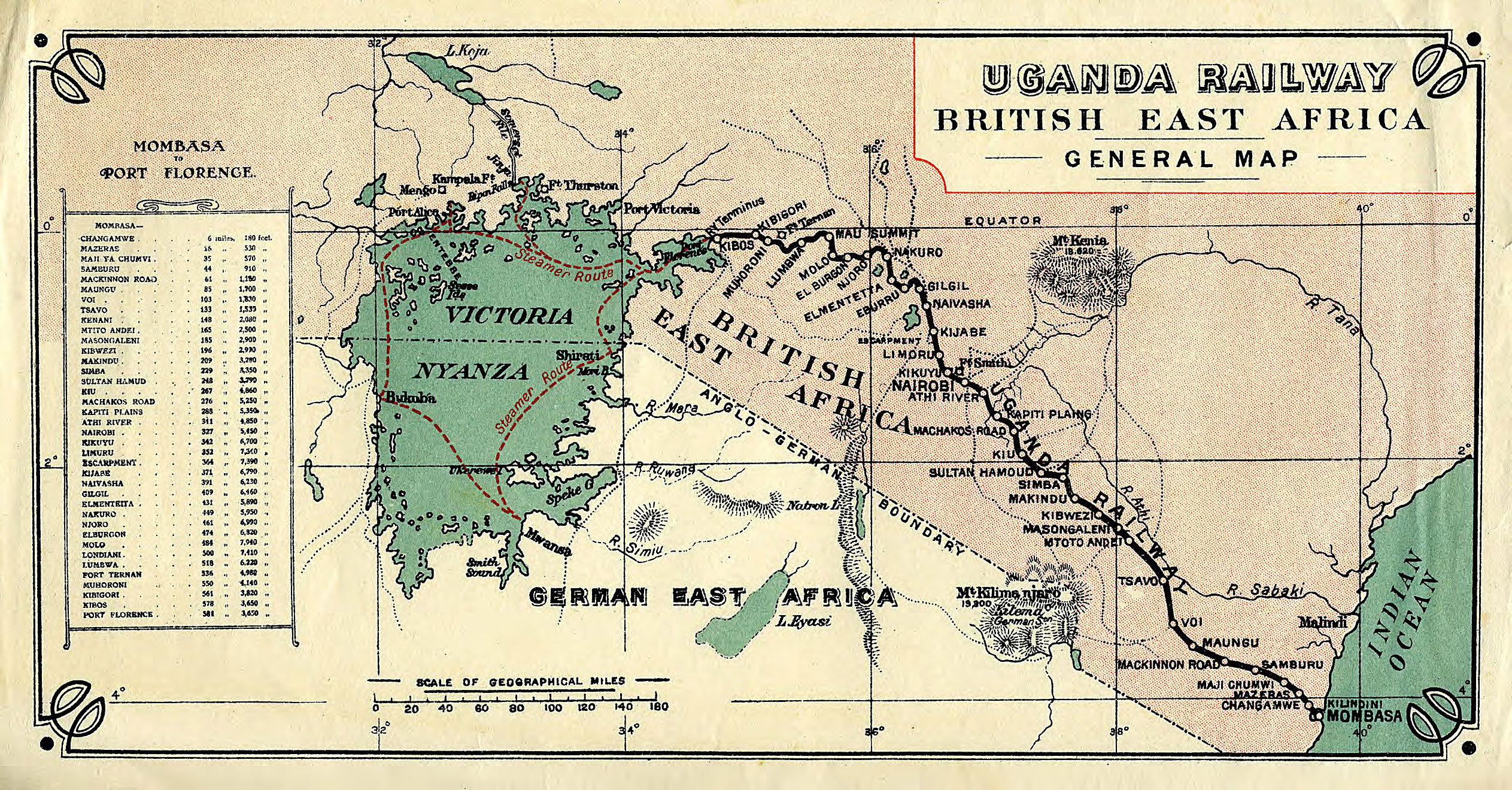

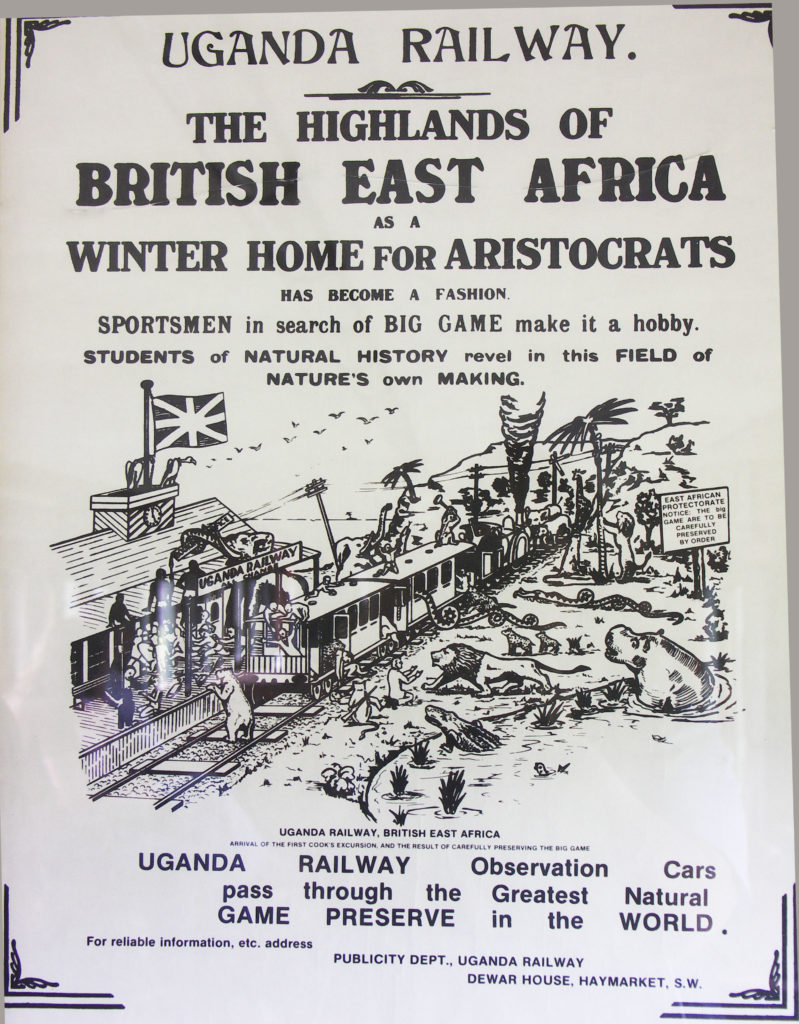

This strategic link between Britain’s East Africa and Uganda Protectorates allowed goods and raw materials to flow between the east coast of Africa and its landlocked interior. Easier access encouraged European settlement and farming, and the railway contributed greatly to the popularity of the safari business by easily transporting supplies and equipment that would have taken an army of porters, each carrying 60 to 80-pound loads, some four and a half months to walk the length of the line from one end to the other. The transformation of a mostly-inaccessible territory prompted the South African Railway Magazine to declare that “the Uganda Railway has literally created a new country.”

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kurve_bei_Mombasa.jpg

Some of the best hunting was in the Nairobi area, and the railway provided an easy way in and out for those who didn’t want to stray too far off the beaten path. The town became the center of the safari industry, as well as the headquarters of the Uganda Railway, eventually developing into the capital and largest city of Kenya. The railway brought economic opportunities, population growth, and urbanization to many of the interior towns along the line, and what were once merely stopping points or small depots are today some of Kenya’s largest cities.

Courtesy of Benitz Family (benitz.com)

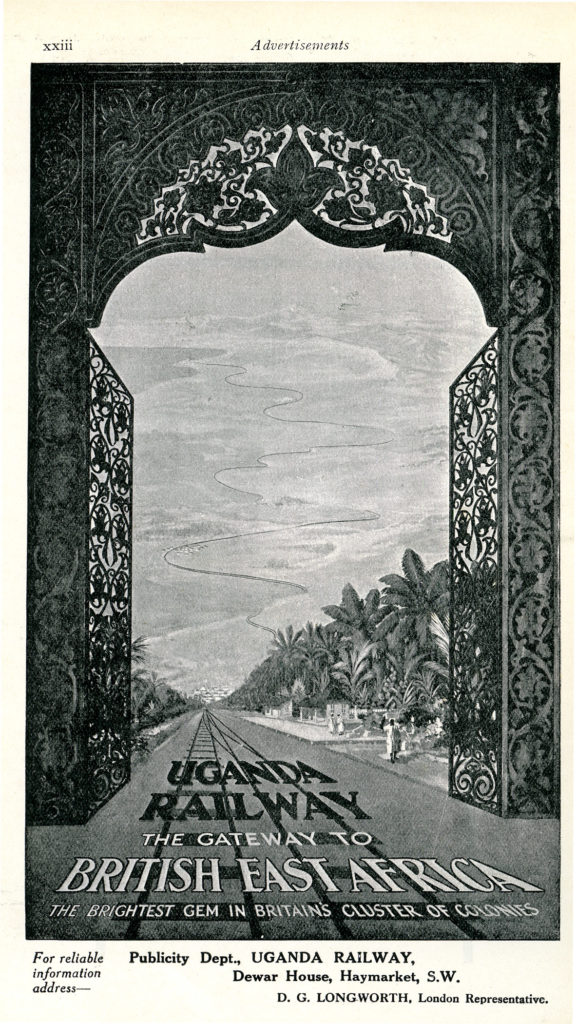

From H. F. Ward and J. W. Milligan, Handbook of British East Africa (The Caston [B.E.A.] Printing & Publishing Co., Ltd., Nairobi, 1912).

Uganda Railway poster on the Twshane Express historic steam train operated by Friends of the Rail in Pretoria, South Africa by NJR ZA is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Courtesy of Harjinder Singh Kanwalhttp (www.sikh-heritage.co.uk)