North America’s only marsupial (female has a pouch) mammal. One of the shortest lived mammals for its size, typically 2 to 4 years. Killed by many predators: humans (and cars), dogs, cats, owls, and larger wildlife.

Short-tailed Shrew (Blarina brevicauda)

This animal has a voracious appetite. Said to eat several times its weight every day, the short-tailed shrew is aided in subduing its prey by a poison found in its saliva.

Least Shrew (Cryptotis parva)

Uncommon in the Commonwealth, this, too, is a shrew with a short tail. It can be distinguished from the short-tailed shrew (Blarina) by its much smaller body and brown color. The short-tailed shrew is slate gray.

Masked Shrew (Sorex cinereus)

The masked shrew’s “mask” is not a very noticeable feature but the nose is long, extending well beyond the mouth, and quite mobile.

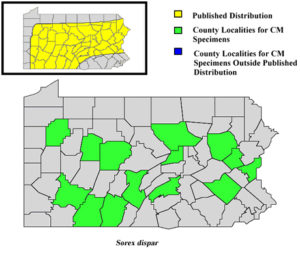

Long-tailed or Rock Shrew (Sorex dispar)

This mammal is not common. Although most often trapped on talus slopes, it has also been found in recently disturbed areas such as forest clearcuts.

Smoky Shrew (Sorex fumeus)

The smoky shrew nests under rotting logs, in rocky crevices, stone piles, and under discarded lumber.

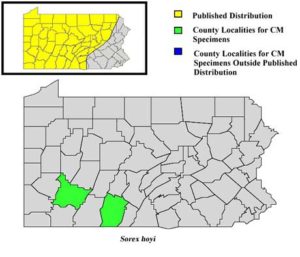

Pygmy Shrew (Sorex hoyi)

The smallest mammal in Pennsylvania and throughout the United States. There are fewer than two dozen pygmy shrew specimens from Pennsylvania in museum collections and all of these have been collected in the last 15 years.

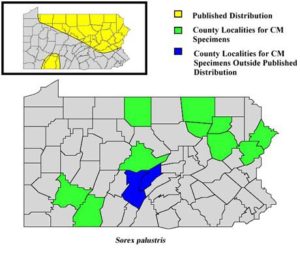

Water Shrew (Sorex palustris)

This uncommon shrew has a fringe of stiff hairs on the outer side of each hind foot that is a direct adaptation to its aquatic lifestyle. Air bubbles trapped by its fur give this animal great buoyancy but only allow it to be submerged for about 15 seconds at a time.

Hairy-tailed Mole (Parascalops breweri)

This species and the eastern mole do not occupy common ground in Pennsylvania (see distribution maps). This is the most common mole in the Commonwealth where worms and beetle larvae may attract it to lawns. During the winter months, it pursues invertebrate prey below the frost line by tunneling as much as 18 inches below the surface of the ground.

Eastern Mole (Scalopus aquaticus)

This mammal digs tunnels day and night and in all seasons and may burrow through woodlands, fields, and lawns. Although accused of feeding on vegetable matter, this is probably only a minor portion of the diet. However, damage may occur during tunneling that causes some vegetation to die.

Star-nosed Mole (Condylura cristata)

This long-tailed mole has a distinctive “star” nose. The end of its snout is surrounded by short, fleshy projections that are highly sensitive to touch.

Big Brown Bat (Eptesicus fuscus)

Banding records show that this bat may live as long as nine years. The big brown bat usually hibernates in caves or man-made dwellings once food sources begin to dwindle.

Silver-haired Bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans)

This species migrates south of Pennsylvania for the winter.

Red Bat (Lasiurus borealis)

One to four young are born in June and cling to the mother in flight until they are too large for her to manage.

Hoary Bat (Aeorestes cinereus)

This, the largest and most strikingly colored bat in Pennsylvania, migrates when the weather becomes too cold to forage on insects. It is believed that its migration pattern follows that of insectivorous birds. With its 15-inch wingspan, its flight has been described as erratic and clumsy. However, most sources say that it is rarely observed because of its habit of emerging well after dark.

Small-footed Bat (Myotis leibii)

George C. Leib of Erie County, Ohio, sent a specimen of this bat to naturalists Audubon and Bachman in 1842. They recognized it as a new species and named it after Dr. Leib.

Little Brown Myotis (Myotis lucifugus)

This is our most common species of bat. It frequently establishes nursing colonies at sites to which the females return each year. In 1939 during planning for the Pennsylvania Turnpike, Charles Mohr banded and transplanted an estimated 2,500 Myotis from tunnels that had originally been constructed for a railroad. Unfortunately, the bats did not accept this relocation some 80 miles away from the tunnels which had existed, largely undisturbed, since 1885. In late 1940, bats were still seen flying through the completed turnpike tunnels.

Northern Long-eared Bat (Myotis septentrionalis)

The ears of this bat are longer than those of any other member of the genus Myotis in Pennsylvania.

Indiana Myotis(Myotis sodalis)

This bat was not recognized as a species until 1928. In 1966, its rarity was mentioned by Doutt, Heppenstall, and Guilday in Mammals of Pennsylvania. Today, it is a federally endangered species. It is known from several caves in the Commonwealth today and these sites are gated to protect the species from disturbance.

Evening Bat (Nycticeius humeralis)

Reported from only a few southern counties in Pennsylvania, this is probably an accidental visitor and not a regular resident.

Eastern Pipistrelle (Perimyotis subflavus)

This bat is known to live up to seven years. Its flight is said to be weak and fluttery, thus earning it the nickname the “butterfly bat.”

Snowshoe Hare (Lepus americanus)

The snowshoe hare is also called the varying hare. This animal is rusty brown in summer but in the autumn, its guard hairs are replaced by new white hairs which give the mammal an overall white appearance. In addition to allowing this mammal to blend into a snowy landscape, the structure of the white hair includes more air which provides for greater insulation during the colder months. In early spring, the hare goes through another molt which returns it to a summer coat. During the fall molt, the fur on its feet becomes much thicker, aiding in insulation. The extra fur also allows the snowshoe hare to move easily on top of deep snow.

Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus)

This species has benefited greatly from the clearing and farming of the Commonwealth.

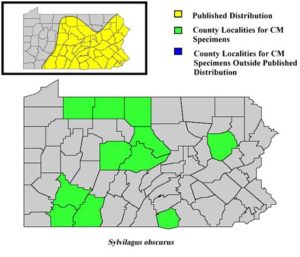

Appalachian Cottontail (Sylvilagus obscurus)

This species was recently recognized as separate from the New England cottontail.

Woodchuck or Groundhog (Marmota monax)

The woodchuck is the largest member of the squirrel family. It builds an extensive burrow system that, once abandoned, provides refuge for many other mammals. This is probably our best-known hibernating mammal.

Gray Squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis)

The gray squirrel easily tolerates life around humans in parks and other small stands of trees where it may build huge leaf nests as well as denning in hollow trees.

Fox Squirrel (Sciurus niger)

One squirrel may bury hundreds or even thousands of nuts. Although many are found again, squirrels contribute heavily to the planting of new trees when unfound food caches sprout and grow.

Thirteen-lined Ground Squirrel (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus)

Not native to Pennsylvania, this species was introduced when a pair escaped from captivity in 1919 around Polk, Venango County. By the time of the Pennsylvania Mammal Survey (1947–1952), scattered colonies existed in western Venango and northeastern Mercer counties. They were not known to have crossed any rivers, therefore distribution seems to be bounded on the north by French Creek, the south by Sandy Creek, and the east by the Allegheny River.

Eastern Chipmunk (Tamias striatus)

This small ground squirrel builds an extensive burrow system, with multiple entrances, where large caches of food are sometimes stored. Food may also be stored in a small hole which the chipmunk excavates and then covers. Unlike the gray squirrel that hides a single acorn in each hole, large stores may be transported in the cheeks of a chipmunk for storage at a single site. Trees are sometimes climbed in search of food.

Red Squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus)

Although they are tree squirrels, these animals also burrow and may store food underground.

Northern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus)

Not frequently seen by people, the northern and southern flying squirrels are not easily distinguished from each other at a distance. Young flying squirrels are sometimes found on the ground, in a disoriented state, after a heavy storm.

Southern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys volans)

This species is common in the woodlands of southwestern Pennsylvania but it is not frequently seen because it is active at night. The animal “flies” by spreading its limbs out to the sides and flattening the furry membranes into a sail that allows it to glide down and forward for distances of up to 40 feet.

Beaver (Castor canadensis)

The beaver is a large rodent adapted for aquatic life. Although awkward on land, it is capable of felling trees eight feet in diameter for construction of its lodge. Details of its engineering prowess make fascinating reading. So, too, is its remarkable recovery in Pennsylvania. The beaver was trapped for its luxuriant fur by early settlers and disappeared from Pennsylvania by the mid-1800s. In the summer of 1917, a pair of beaver from Wisconsin was released in Cameron County. Within five years, the beaver populations of Cameron County and southern McKean County were well established from that original pair. That group and subsequent releases from Canada and New York in 1919, 1920, 1922, and 1924 form the nucleus of the current inhabitants in the Commonwealth.

Allegheny Woodrat or Pack Rat (Neotoma floridana)

The mysterious decline of Allegheny woodrat populations throughout eastern North America has been the focus of much research in recent years. In Pennsylvania, there are only a few known sites where woodrat dens persist. As yet, none of the theories explaining this native rat’s diminished populations has been proven.

White-footed Mouse (Peromyscus leucopus)

Found throughout the Commonwealth, this is one of the most common mammals in Pennsylvania.

Deer Mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus)

There are three different subspecies of deer mouse that occur in Pennsylvania. The two most abundant varieties prefer a woodland habitat. The third subspecies prefers open fields and other areas with little cover.

Red-backed Vole (Clethrionomys gapperi)

Like many herbivores, this mouse will gnaw on bones and deer antlers to obtain calcium.

Rock or Yellow-nosed Vole (Microtus chrotorrhinus)

This species has often been linked to the long-tailed or rock shrew Sorex dispar because of their common preference for rocky habitats. This vole looks a great deal like the more common meadow vole, except for the distinctive yellow splash of color across its nose and cheeks.

Meadow Vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus)

One of the most abundant and widespread mammals in the Commonwealth, it serves as prey for carnivores as tiny as the least weasel and as large as the black bear.

Pine or Woodland Vole (Microtus pinetorum)

This mammal builds a large network of subterranean tunnels where it caches food for the winter. It can be a serious agricultural pest when it girdles orchard trees in order to consume the bark during the winter months.

Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus)

This rodent is well adapted to semiaquatic life but is not closely related to the beaver. It, too, is valued for its fur. One of its chief enemies is the mink.

Southern Bog Lemming (Synaptomys cooperi)

Although this mammal looks similar to several of the voles that occur in the Commonweath, it can be distinguished by its grooved upper incisors, extremely short tail, and grizzled, gray-brown fur.

House Mouse (Mus musculus)

This Old World rodent is the common pest found living in houses, barns, and other human habitations. It arrived in the New World as a stowaway on board ship and has lived successfully around people for centuries.

Norway Rat (Rattus norvegicus)

This animal is a good swimmer and climber whose opportunistic behavior has led to its successful worldwide distribution. This Old World rodent did not originate in Norway but in China. It is a serious pest of granaries and other food storage sites and a vector of numerous diseases communicable to humans. Most sources state strongly that efforts should be taken to control of Norway rat populations whenever possible.

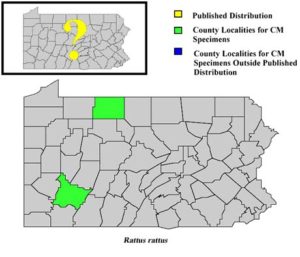

Black Rat (Rattus rattus)

This species is thought to have been extirpated from (forced out of) the Commonwealth by pressure from the more aggressive Norway rat. Although some individuals may continue to find their way to coastal seaports such as Philadelphia via incoming ships, it is unlikely that populations will be successfully re-established.

Woodland Jumping Mouse (Napaeozapus insignis)

A long tail and powerful hind legs provide this Pennsylvania native with the ability to jump six to eight feet when avoiding a predator. Its closest relative is the meadow jumping mouse and both are true hibernators.

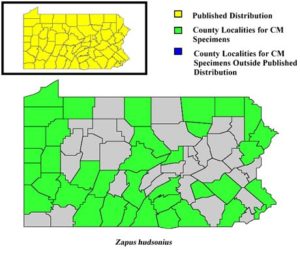

Meadow Jumping Mouse (Zapus hudsonius)

This tiny rodent is reported to be an excellent swimmer.

Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum)

Porcupines cannot throw their quills, but as the tail is swished violently to threaten an enemy, loosely attached quills may fall off the body. Young are born with soft, short quills that dry and stiffen within a few hours.

Coyote (Canis latrans)

The coyote is an extremely secretive animal and is rarely seen in Pennsylvania. Several canids brought to the Section of Mammals for identification in recent years have proven to be coyotes from various parts of the Commonwealth. There have also been several apparent coyote–dog hybrids, also called coydogs, presented for identification. Determinations are based mostly on examination of the skulls.

Gray Wolf (Canis lupus)

This species has been extirpated (disappeared) from Pennsylvania since about 1892. Stories about wolf kills persisted through the 1940s.

Gray Fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus)

It is reported that this mammal can climb trees.

Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes)

The den of the red fox is frequently a converted woodchuck burrow that takes advantage of the multiple exits created by the original inhabitant. Red foxes will dig their own dens or make use of hollow logs as well.

Black Bear (Ursus americanus)

The black bear is not a true hibernator like the woodchuck. Although it goes through a period of dormancy, it does not lower its respiration, heart rate, or body temperature in the manner that defines true hibernation.

Raccoon (Procyon lotor)

Raccoons are highly adaptable and have become quite accustomed to life around people. During the last decade, its association with rabies in the Commonwealth has made it a less favored neighbor than might otherwise be the case.

Pine Marten (Martes americana)

Although this mammal was thought to have disappeared from the state around 1900 due to loss of forest habitat, two specimens have been collected in the latter half of the century. The Pennsylvania Biological Survey classifies its status as undetermined at present.

Fisher (Pekania pennanti)

This animal recently has been reintroduced in Pennsylvania. Tracking of the released individuals indicates that the fisher are doing well.

Ermine or Short-tailed Weasel (Mustela erminea)

In summer, the ermine is dark brown above and white washed with yellow below. In the winter, it turns completely white except for a black tip on the tail.

Long-tailed Weasel (Mustela frenata)

Several sources indicate that weasels have a reputation for killing more than they can eat at a given time. This is probably a mistaken impression from observations of weasels moving a kill to its den. However, the animal may move a carcass to its burrow to feed the young or to cache for future meals.

Least Weasel (Mustela nivalis)

This is the smallest carnivore in Pennsylvania with a total length of only eight inches and weight of only two ounces!

Mink (Neovison vison)

Like the skunk and other mustelids, the mink possesses anal scent glands that produce a pungent odor when the animal is stressed.

Badger (Taxidea taxus)

Since 1946, there are four records of the badger in Pennsylvania, all in counties of southwestern Pennsylvania adjacent to more uniformly suitable habitat in Ohio.

Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis)

Valued for its fur, the skunk is also an important predator of rodents and insects.

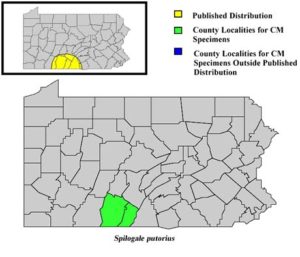

Spotted Skunk (Spilogale putorius)

This relative of the striped skunk is known to occur only in Fulton and Bedford counties in south-central Pennsylvania. It is the smallest skunk, averaging only 1-3 lbs. As with the striped skunk, the patterns of black and white vary greatly among individuals.

River Otter (Lontra canadensis)

This animal is well adapted for aquatic life with a streamlined body, thick coat and oily underfur, webbed feet, a muscular, rudder-like tail, ears and nose that can be closed when submerged, and strategic placement of the eyes.

Mountain Lion (Puma concolor)

Although reports of sightings in Pennsylvania have persisted to the present day, virtually all have been undocumented. The most recent mountain lion kill in Pennsylvania occurred in 1967 and has been determined to be a released captive of a southern subspecies. The last known Pennsylvania mountain lion was killed in the 1856 in Susquehanna County. This specimen was preserved as a body mount that has recently been refurbished and is exhibited on Penn State’s main campus.

Lynx (Lynx canadensis)

Although there are records of lynx in the Commonwealth, it is believed that all are cases of this predator temporarily expanding its range due to low prey densities further north.

Bobcat (Lynx rufus)

This species is rarely observed because of its shy and elusive nature. Bounty was paid on bobcats in the Commonwealth between 1810 and 1938. Its numbers are currently considered to be low, and concern for the impact of development in regions of preferred habitat have caused it to be designated “vulnerable” by the Pennsylvania Biological Survey.

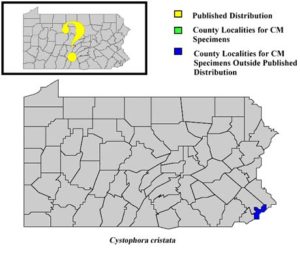

Hooded Seal (Cystophora cristata)

This species is known to wander south of its typical Arctic Ocean habitat and has been sighted several times in the Delaware River. In 1951, a female was taken from the Delaware River near Bristol, Philadelphia County. It was sent to the Section of Mammals by the curator of mammals at the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia. It is preserved as a skin, skull, and body skeleton in our research collection.

Elk (Cervus elaphus)

The original elk herd disappeared from Pennsylvania in the late 1800s. Today, the Game Commission manages a reintroduced herd in McKean, Elk, and Cameron counties.

White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus)

This is undoubtedly our most popular game species. The spots found on a white-tailed deer fawn represent a form of cryptic coloration. Meant to simulate the appearance of sunlight filtering through trees onto the forest floor, a fawn can go undetected while lying motionless only a few feet from a potential predator.