Biographies

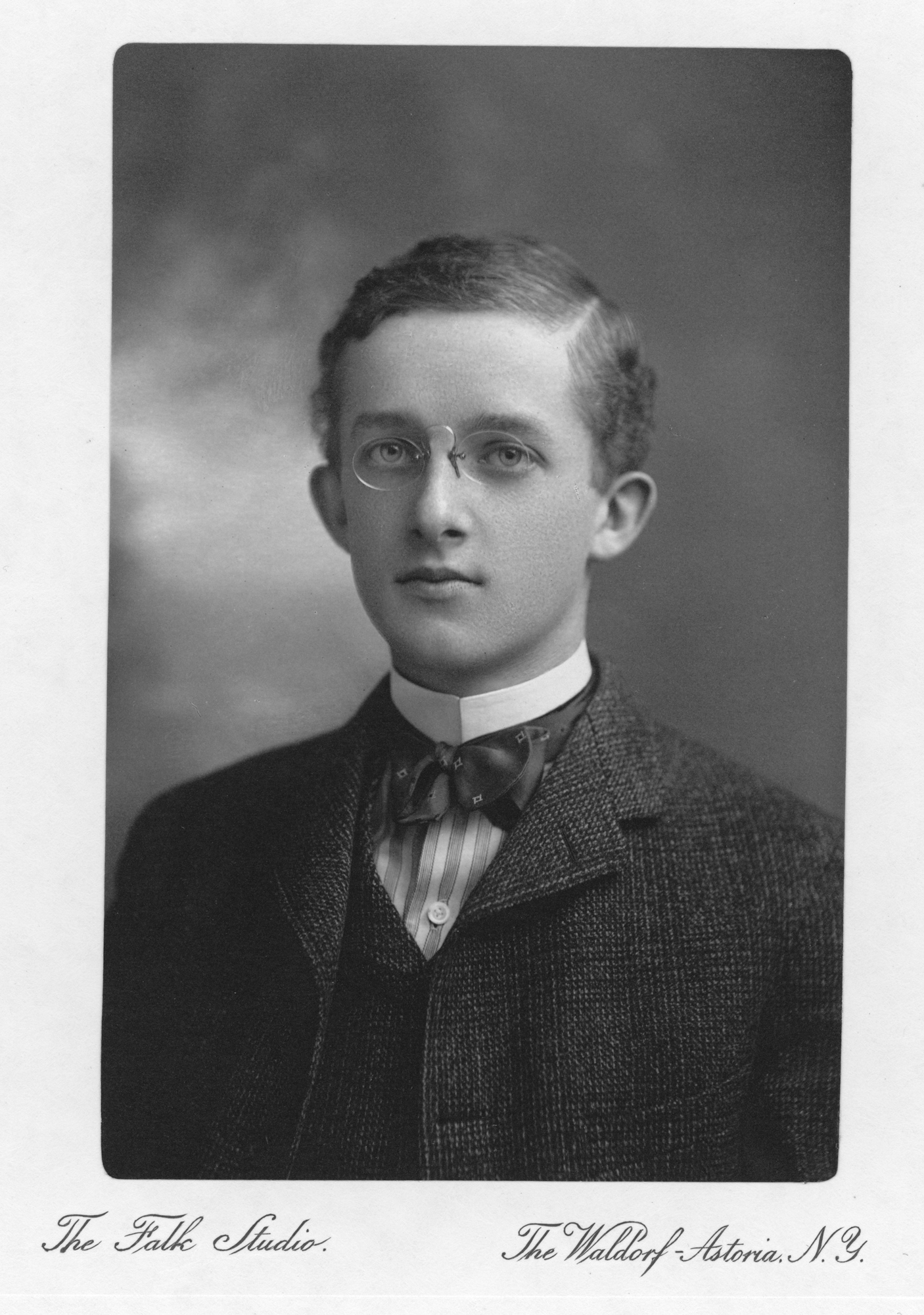

CHILDS FRICK (1883–1965)

Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York

Born in Pittsburgh, Childs Frick was the first of four children of industrialist Henry Clay Frick and Adelaide Howard Childs. He spent his childhood at Clayton, the family estate in Pittsburgh, exhibiting an early interest in studying the rocks, plants, and animals in the surrounding wooded areas and experimenting with photography and taxidermy.

Frick attended Sterrett School and Shady Side Academy in Pittsburgh and graduated from Princeton University in 1905, the same year his father moved the family from Pittsburgh to New York City. Early hunting trips to Canada and the American West fueled Frick’s growing enthusiasm for adventure and led to his first trip to British East Africa (Kenya) in 1909–10, where he encountered the remarkable big game of Africa. Motivated by the success of the Smithsonian’s African Expedition, led by Theodore Roosevelt during that same time period, Frick planned a more ambitious safari that began in Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1911 and ended in British East Africa in 1912. He was gone nearly a year from the time he left New York by steamship until his return to the United States. The specimens collected on these two trips became the foundation of the African mammal collection at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

In 1913, Frick paused from traveling to marry Frances Shoemaker Dixon (1892–1953) in Baltimore. Shortly thereafter the couple returned to Pittsburgh so that he could manage the Frick family’s business affairs. It caused a strain in the relationship with his father, however, since Childs was more interested in the natural sciences than in business. During World War I Frick was sent to California to serve in the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps, accompanied by his wife and two young children. There he studied the geological and paleontological history of the Pacific Coast through a University of California program. By this time his primary focus had turned to fossil mammals, and he was more interested in wilderness and wildlife preservation than in collecting big game.

Photo by Daderot us licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

After the war Frick and his family returned to the East Coast where his scientific career continued. His father was so delighted at their return that he purchased a mansion for the couple in Roslyn, Long Island, twenty miles east of New York City. They named it Clayton, after Frick’s boyhood home, and raised four children there: Adelaide, Frances, Martha, and Henry Clay II (“Clay”). There was plenty of space for Frick to indulge his love of sports, and the grounds eventually included tennis courts, a polo field, swimming pool and ponds, a private zoo, and even a ski slope with its own snowmaking machine. He and his wife shared a passion for horticulture and worked with renowned landscape architect Marion Cruger Coffin to create the formal French gardens.

It was while living at Clayton that Frick began his association with the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), becoming a long–time trustee and benefactor and establishing the Frick Laboratory of Vertebrate Paleontology. His field trips contributed over 200,000 fossil specimens to the museum and are now housed in the Childs Frick Building, completed in 1973.

Courtesy of The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York

Frick maintained close ties to Carnegie Museum and was named Honorary Curator of Mammals in 1920, in recognition of his interest in the work of the museum and his contributions to the collections. He visited Pittsburgh frequently and kept up an active correspondence with museum director Andrey Avinoff, who also had a home on Long Island. He made regular financial gifts to the museum, and the Paleontology Department especially benefited from his support of fossil–hunting trips that otherwise wouldn’t have been possible. Loans from the museum’s collection of fossil and Recent mammals were frequently sent to him to study at AMNH or at Millstone, his personal research laboratory at Clayton, and he authored numerous publications on his findings.

Frick would later come to own property in Bermuda, called “Castle Point,” where his love of nature was demonstrated in his conservation efforts. He worked with the Bermuda Agricultural Station in experimenting with different types of vegetation that could withstand the island’s salt spray and took a lead role in the preservation of bird life, especially the cahow, or Bermuda petrel, a nocturnal seabird on the brink of extinction.

In addition to his recognition as a respected paleontologist, Frick accumulated a long list of honorifics and was associated with numerous societies and clubs dedicated to natural history and conservation. Four years after his death at the age of 82, Nassau County purchased the Clayton estate, where he lived for almost fifty years, and established the Nassau County Museum of Art. Frick is buried in the family plot in Pittsburgh's Homewood Cemetery.

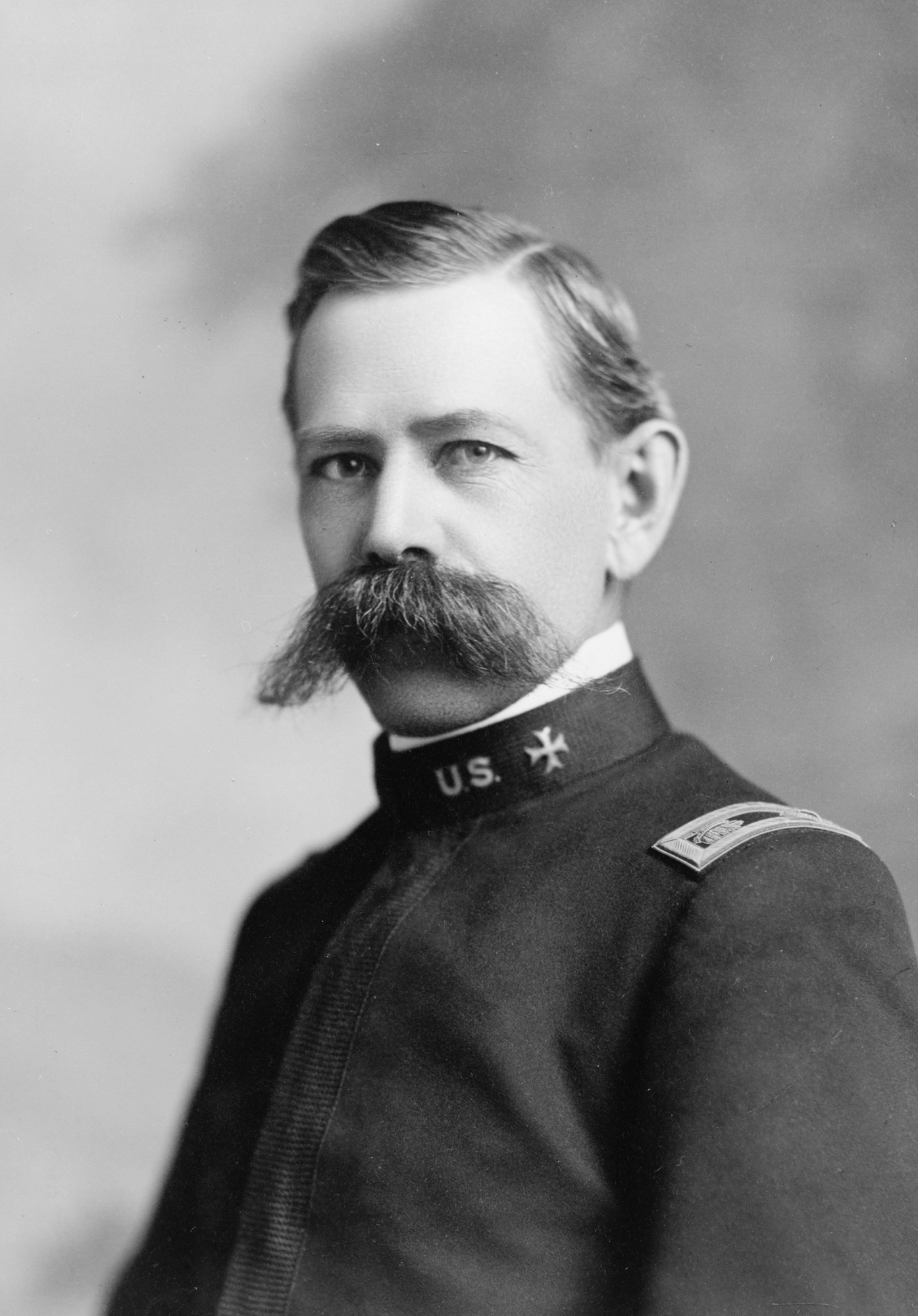

EDGAR ALEXANDER MEARNS (1856–1916)

Ruthven Deane Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-115922

Photographer unknown

Edgar A. Mearns, army surgeon and naturalist, was born in Highland Falls, near West Point, New York, to Alexander and Nancy Reliance (Carswell) Mearns. He developed an interest in birds and animals at an early age, learning their names and behaviors, and spending hours in the woods. When he was about ten years old he began to document his observations on birds and, as a teenager, accumulated a collection of carefully labelled flora and fauna specimens.

Mearns’ interest in biology led to medical courses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of New York (later to merge with Columbia University). While still in college he published his first scientific paper, “The Capture of several Rare Birds near West Point, N.Y.,” and met other young naturalists of the newly formed Linnaean Society of New York. After graduating in 1881, Mearns married Ellie Wittich who shared his interests in natural history and assisted in his collection work. They had two children, Louis di Zerega Mearns and Lillian Hathaway Mearns.

Mearns Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-105870

Photo: Edgar A. Mearns (1856-1916)

In 1882 Mearns joined the U.S. Army’s medical department, and served as a temporary curator of Ornithology at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) while awaiting his first military assignment. He later received his commission as assistant surgeon at Fort Verde, Arizona. His spare time was spent exploring ancient ruins and the unfamiliar plants and animals of the desert. Twenty–six years of active military service sent him to additional posts in Texas, New Mexico, California, Virginia, Rhode Island, Yellowstone National Park, and the Philippines, among others, collecting wherever he went and writing papers about his discoveries.

Mearns’ first association with the Smithsonian Institution, also known as the United States National Museum (USNM), was in 1892 when he was charged by the army to conduct a biological survey along the U.S.–Mexican border. He and his party spent two years collecting 30,000 plant and animal specimens that were presented to the museum. Upon completion of the survey he reported to Fort Meyer, Virginia, which allowed him to gather data and study the specimens at the nearby USNM. Mearns planned to publish a detailed multi–part report on his findings, but due to lack of funding from Congress only the first part on mammals was published.

From Proceedings of the scientific meetings of the Zoological Society of London, Part III, 1878

openlibrary.org

Duty sent Mearns to the Philippines in 1903–04, where he not only served as a military surgeon but was instrumental in the formation of the Philippine Scientific Association. He obtained general biological collections as well as ethnographic material. Exhausting work and complications of tropical parasitic disorders caused him to be hospitalized at the end of the excursion. While still in recovery, he published five papers describing new mammals and birds from the Philippines. In 1905 Mearns returned to the Philippines for a two–year period and was placed in command of a “Biological and Geographical Reconnaissance of the Malindang Mountain Group,” in western Mindanao, which was organized to explore and map the region and collect its natural products.

Mearns’ next great adventure was with the Smithsonian–Roosevelt African Expedition. The Smithsonian recommended Mearns as a field naturalist and collector, and shortly after Theodore Roosevelt left presidential office the party sailed for Africa on March 23, 1909. While Roosevelt concentrated on big game, Mearns collected birds, small mammals, and plants. Of the 4,000 birds obtained, Mearns himself was responsible for over 3,000 of them. The expedition returned to the U.S. in 1910, and while Mearns was still studying his finds in Washington he was asked by Childs Frick to accompany him on another exploration of Africa. The opportunity to add to his research material was hard to resist and once again Mearns left New York City, in 1911, and returned almost a year later. This time over 5,000 birds, nests, and eggs were accumulated.

Having retired from active service in 1909 with the rank of Lieutenant–Colonel, Mearns at last had time to research and write about his collections. Poor health interrupted his studies, however. Tropical diseases, grueling collecting trips, and the complications of diabetes took their toll, reducing his productive work time more and more. Mearns died at the age of 60 at Walter Reed Army General Hospital leaving behind a wealth of research material. He was in the midst of preparing a comprehensive report on the birds collected in Africa, and masses of his notes from the Philippines were still unpublished. During his lifetime he authored well over a hundred scientific papers, and ultimately over fifty new taxa were named in his honor.